Most of us have heard of anthropomorphism, giving animals human characteristics, but few of us have heard of, or given much thought to, zoomorphism, giving humans animal characteristics. And yet we probably commit the crime of zoomorphism much more frequently than we do anthropomorphism. In fact, once we move past the well known literary examples of anthropomorphism, such as Aesop’s fables, George Orwell’s Animal Farm (this may also be an example of zoomorphism), the iconic Disney movie Bambi (which has had a huge impact on political thinking about animals and hunting), and how we think about, talk to, and treat our pets—we’re left to consider an endless list of words, phrases, and expressions we use to refer to each other as—or as like—animals.

Egyptian gods often had animal bodies and/or heads.

While some words and expressions draw attention to them selves as comparisons and are thus not particularly deeply integrated into our language and how we see each other, others are so deeply ingrained in our language and thought that we hardly notice them. Not only can we classify zoomorphic words and expressions, but I’d suggest we can also order those classes into a kind of hierarchy extending from the least integrated and most noticed to the most integrated and least noticed. The classification might also range from traditional expressions to relatively new expressions in modern usage.

Many Indian gods have animal features and powers.

We’ve inherited many common zoomorphic expressions from the distant if not obscure past. She’s got ants in her pants. A little bird told me so. He and she are birds of a feather. He was running around like a chicken with its head cut off. She has the memory of an elephant. Don’t let him get your goat. They have their heads in the sand. He’s mad as a March hare. He’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing. She looked like a deer caught in headlights. I have a frog in my throat. And so on. These expressions have been around for decades if not centuries and attest to a long history of zoomorphic indulgence. And of course we have zoomorphic aphorisms: A bird in hand is better than two in the bush. You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. And there are countless colloquial or regional expressions. My brother-in-law from the mountains of Pennsylvania shared these with me: as fine as frog’s hair, raining like a cow peeing on a flat rock, and slower than a herd of turtles.

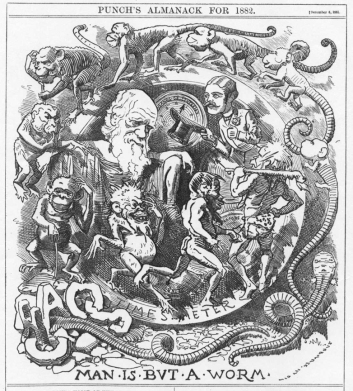

Zoomorphism and evolution

We use zoomorphic similes relentlessly, yet writers, editors, and readers alike view these expressions as unabashedly cliché: blind as a bat, busy as a bee, snug as a bug, sly as a fox, quiet as a mouse, scared as a rabbit, wise as an owl, stubborn as a mule, bray like a donkey, drink like a fish, and pee like a racehorse. Note that those similes describing nouns (people) use the comparative “as,” while those describing (people’s) actions use “like.” Some employ rhymes. Others simply aren’t true, the best known being wise as an owl, as scientists and naturalists claim owls are rather stupid for a bird (do they use a standard human IQ test to determine animal intelligence?). Regardless, the writing instructor and the editor will mark these common similes as cliché.

Not quite birds of a feather

As we move deeper into our zoomorphic body of language, we arrive at our use of animal nouns to call each other names. He’s an ass, a jackass, a bear, a buck, a tom cat, a chicken, a sitting duck, a fox, a stud, a peacock, a swine, a pussy, a rat, a slug, a snake, a card or pool or loan shark, a paper tiger, a shellback, a weasel, a wolf, a lone wolf. She’s a bird, a cow, a fox, a clotheshorse, a butterfly. He or she can be a crab, an old goat, a silly goose, a lamb, a pig, a hog, a real tiger while they are sheep (see John Updike’s short story “A&P”). Note that a majority of the list breaks down on sexual lines and that many expressions are mean, vulgar, and/or chauvinist. Note also that these expressions do not merely compare, using the terms “like” or “as,” but rather out and out equate humans with animals. Other animal noun expressions referring to human life include catfight, chicken-scratch, doe eyes, dogs (meaning feet), eagle eye, hawk eye, paws, horsepower, lion’s share, piggybank, rat-tail, swan song, and swan dive. We might conclude at this point that it’s hard to think about ourselves without thinking about animals.

Our zoomorphic tendencies reach such depths of integration in our language that we hardly notice when the words we’re using refer back to animals. Many of our zoomorphic adjectives fall into this category: catty, clammy, bull-headed, crabby, doe-eyed, dogged, dog-eared, dog-tired, fishy, foxy, lionhearted, mousy, mouse-brown, owlish, piggish, hoggish, prickly, ratty, sheepish, slothful, wolfish, and raven-haired. Because animal names or characteristics have been converted to adjectives in this case, they tend to draw less attention to themselves as animal words and we hardly think of the animal when we use them. Yet the animals to which these words refer are nevertheless sorely used, whether they’re aware of it or not.

I’d suggest the deepest we go in our sublimating of animal words and characteristics is via our zoomorphic verbs, animal words describing our actions. These words are so deeply imbedded that they’re almost imperceptible when we use them. We ape, parrot, badger, paw at, dog, outfox, gull, goose, and rat on one another. We buck the system, clam up, crane our necks, weasel (equivocate), and crow (boast). We fish for items other than fish. We horse, monkey, and cat around (two-word verbs or idioms). We hog up the food and wine. We squirrel money away. We’ve taken a quality from an animal and applied it to how we act or move. By giving each other what we perceive as animal characteristics, we’ve taken the animals fully into ourselves. We’ve applied animal nature to our own nature where it means the most: our actions.

Similarly, we humans make a cacophony of animal sounds for which we’ve created words. We too howl, growl, hoot, hiss, bark, squeal, bray, crow, snarl, and purr, to list a few. The example of a braying human that comes to mind is Nick Bottom in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, whose head is turned into that of a jackass while Queen Titania has been given a love potion to fall in love with him. And for a while she loves him all the more for his braying—till the potion wears off.

Other ways in which animal words have penetrated the human sphere can be found in a variety of expressions we use today: bear, meaning big cuddly, lovable man; coyote, meaning one who guides an illegal north across the border into the United States; cougar, meaning an older woman hunting younger men; mole, meaning a spy penetrating an organization or government; mossback, meaning an extremely conservative or old-fashioned person; and lemming, meaning a mindless follower. We also have such expressions as crying big crocodile tears, hens’ night (equivalent to men’s bachelor party), and monkey mind (busy, distracting thoughts that get in the way of clearing the mind in yoga).

Hanuman, Indian monkey god

Finally, many animal images and words have acquired great symbolic and cultural depth and weight. For example, the eagle is the symbol of the United States of America (since the eagle is as much a carrion thief as a raptor, I’m not sure what this says about the country). The donkey represents the Democrats while the elephant represents the Republicans. Hawks are warmongers and doves are peaceniks. A bear market refers to a declining economy while a bull market describes a vigorously growing era. In the New Testament, lambs refer to followers of Jesus. Fraternal lodges and sports teams boast whole menageries of animal mascot names, yet it’s ironic that the animals whose names they’ve commandeered can’t rise up against such blatant stereotyping because they can’t speak or write human.

Why do we make people animals or like animals? Perhaps the impulse derives from an inherent tendency to make fables of our selves. We may do it out of an infantile impulse to give concreteness to our abstract thinking, the way we use animals to tell stories to our children—or as Aesop did to convey his morals. Maybe debasing animals gives us a means to debase one another. Many of our animal words and expressions have a negative twist, which I would suggest says more about how we feel about animals than how we feel about one another. When we call a man a pig, what are we saying about pigs? That pigs are dirty because they eat slop and slop about in the mud? But do they trash our water, air, and land, our yards, cars, and houses, or our bodies and minds (not to mention outer space) as we humans do? Hardly. Then perhaps it’s more denigrating to call a pig a human than a man a pig. The fact that we don’t see it that way hints at a kind of human zoophobia, a fear of or hatred toward animals that comes clear through a study of our language. I remember how triumphant I felt when I read Part IV of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, in which the horses are the masters and the humans the slaves—how language, irony, and satire can hold a mirror to our faces.

In other words, we stereotype animals at least as much as we stereotype people. Yet animals have no recourse to fight back. They may forever remain the victims of our need to denigrate one another with their images and the words we attribute to them. Although there exist animal rights organizations, these groups are concerned with the treatment of animals and not the language we use to describe them or the fact that we use their names to call each other epithets or to suggest something negative about each other’s behavior or character.

Santa the Lamb

On the other hand, as much as animals enrich our lives on Earth (probably more than we enrich theirs), the language we borrow from them to refer to ourselves also enriches our language. Animals give our language color and expand it to include another dimension. Conversely, language, like a mirror, helps to remind us of our animal nature, true or false. Whether in anger we call a man an ass or with adolescent fervor refer to a girl as a fox, animal words have weaseled their way so deeply into our collective psyche that we no longer notice—and the weasel winks at us from beneath our consciousness. In the end, when we howl or growl “You animal!” there’s more truth in it than we might think.

I welcome comments and especially further examples of and angles on this subject.–r